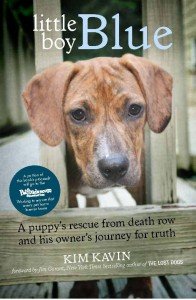

Excerpt from Little Boy Blue by Kim Kavin

This post first appeared on Pet News and Views

I had heard again and again about Northeast Animal Shelter in Salem, Massachusetts, a facility that rescuers all across the South feel is the gold-standard way station for dogs like Blue who are in transit to permanent homes. And it came to exist, I learned in a telephone call, because a woman named Cindi Shapiro happened to read The Wall Street Journal on Thursday, March 6, 1970.

Shapiro was just twenty-five years old, a recent graduate of Harvard Business School. She loved animals, so her eyes gravitated naturally toward one particular front-page headline. “With Right Tactics, It’s Easy to Market A Three-Legged Cat: Little Animal Shelter Succeeds By Imitating Big Business.”

The article, by staff reporter William Mathewson, told the story of Alexander Lewyt (pronounced LOO-it). At the time, the resident of Long Island,New York, was sixty-six years old and best known for having invented the Lewyt vacuum cleaner. It was sold door-to-door following World War II with a promise to homemakers that it would not interfere with the reception on their big-box radios or black-and-white televisions.

The Journal article explained how Lewyt became involved with North Shore Animal League on Long Island in 1969, when his wife talked him into donating $100. Lewyt got curious about how his money would be spent, so he paid a visit to the twenty-five-year-old shelter. It was open only two hours a day on five days of the week, had one full-time employee, and barely had enough cash flow to keep the lights on. “They were also acting as the local dogcatcher,” Lewyt told the Journal, “and they were losing money on every dog they’d catch.”

Lewyt thought that was a pretty dumb way to run an operation, so he taught the shelter’s directors about direct-mail campaigns. Working with Publishers Clearing House, which was near the shelter on Long Island, Lewyt produced a letter featuring a photograph of a puppy and a kitten. The letter asked its 28,000 recipients, “Would you give a dollar—just $1—TO SAVE THEIR LIVES?” Lewyt got a celebrity endorser to donate his signature, too. It was singer Perry Como.

That mailing brought in $11,000, which is the equivalent of about $67,000 today. Within the next five years, the shelter’s staff grew from one to twenty-five employees, its hours of operation increased to every day of the year, and its advertising budget alone was earmarked at $50,000 (about $125,000 in current dollars). That’s why The Wall Street Journal had taken notice. Lewyt was running the shelter as if it were a corporation—work he would continue until his death in 1988. “We have the same concept as bringing any product to the public,” Lewyt told the Journal in 1975. “We have our receivables, our inventories. And if a product doesn’t move, we have a promotion. . . . Most animal shelters are run by well-intentioned people who don’t know anything about fund-raising or running the place like a business. The only reason they don’t go broke is that a little old lady dies every year and leaves them something.”

That was all that Cindi Shapiro needed to read.

“This article was an epiphany for me,” she recalls. “It put together everything that I wanted to do with everything I’d been trained to do.”

Shapiro found Lewyt’s number in a thick printed phone book, called him unannounced, and said she wanted to do what he was doing near Manhattan, only up in Massachusetts. He spent the next forty-five minutes berating her from his end of the phone line—the way a father might snap at a daughter who says she wants to turn down a corporate job offer and instead become a painter of abstract expressionist art. Lewyt told Shapiro that rescuing animals was a lifelong commitment, and that the work could be absolutely heartbreaking. He tried to scare off the fresh-faced college graduate by insisting there wasn’t a darn nickel of money to be made.

“When he was done, maybe just because I was still on the line after all that, he invited me to Long Island to see what he was doing,” Shapiro told me. “At the end of the weekend, he told me he’d always wanted to know whether his concept could be duplicated, and that I was the first person he’d met who had a shot at succeeding. He told me, ‘I’m going to give you the ten trials of Hercules, make you do things like a financial projection and a marketing study, to see if you can do it.’”

Not long after Shapiro completed Lewyt’s feats of mental strength, he sent her a check for $5,000. She rented the basement of a veterinarian’s office with room for just ten cages. That was in 1976, a full thirty-five years before I stepped foot into the current incarnation of Northeast Animal Shelter in Salem, Massachusetts. As I pulled into the parking lot, I saw not a single hint of the organization’s humble roots.

Note from Michele Hollow, editor Pet News and Views: I reviewed Kim’s book earlier this month. I wanted to share this excerpt with you because of its importance. Ever since I heard Mike Arms, president of Helen Woodward Animal Center (HWAC), talk about the importance of running animal centers as a business, something inside clicked. It made perfect sense, as we can see and learn from models like Northeast Animal Shelter and HWAC. HWAC has a wonderful program that focuses on this very topic.

Everyone who loves animals should read Little Boy Blue.